By Vicki Matranga, Design Programs Coordinator

Multi-tasking in the kitchen with Sunbeam

What kitchen appliance created such a stir in American homes that nearly 70 years after its premier it merited its own U.S. postage stamp as an icon of household convenience? You probably had one in a kitchen during your lifetime—the Sunbeam Mixmaster.

In 1929 when the Mixmaster was first patented, American women labored long hours to prepare and preserve food and keep household equipment in working order. Most cooking and housework was done by hand. Electricity had powered lighting and commercial machinery for about 30 years. Most new city houses were wired and the cost of electrical appliances had dropped so that middle-class families could afford basic products such as irons and vacuum cleaners. Although small motor-driven kitchen appliances had become popular in the previous decade, the nationally promoted Mixmaster offered great value at a great price, and quickly became the workhorse of the American kitchen.

The Mixmaster epitomized the innovation that marked the Great Depression’s impact on design and technology in the 1930s. In a seeming paradox, the strained economic times propelled the creation of many new products that inspired families to spend their scarce dollars and, at the same time, introduced the streamlined styling that is revered today. The Mixmaster’s solid design and appearance changed very little from 1930 to 1967 though it continued for decades later through many corporate changes. Jarden Consumer Solutions now owns the brand and offers the Sunbeam® Heritage Series®– stand mixers that recall the comforting look of the original.

Practicality that Paid for Itself

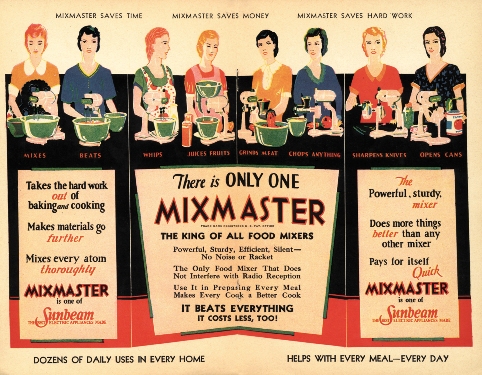

The Mixmaster of the 1930s not only beat cake batters. A multi-tasking miracle, its many attachments (stored in a custom cabinet) were used to shell peas, grind meat and coffee, peel potatoes, chop, slice or shred vegetables, juice fruits, sharpen knives, open cans and polish silver. The machine promised to take the hard work out of kitchen tasks as well as save money—by making foods go further and by helping to prepare flavorful foods that cost less than store-bought cakes or sausages. It offered functional benefits such as bowls that turned by themselves and off-center beaters that spun while scraping the inside of the bowls.

In the color center spread of a user’s manual of that time, notice the claims that are clues to the technological issues of the times: “mixes every atom thoroughly” and “the only food mixer that does not interfere with radio reception.” In today’s kitchens, we still seek “powerful, sturdy, efficient, silent” appliances with “no noise or racket” and expect their operation won’t cause static for TV or internet reception!

Thanks to An Unsung Industry Pioneer

A visionary man whose name is barely known today reinvented kitchen equipment. Born in 1903, Ivars Jepson grew up on a farm in Sweden. A young man with an insatiable curiosity about how things work, he studied engineering in Sweden and Germany, emigrated to the U.S. and came to Chicago in the mid-1920s. He joined the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company (renamed Sunbeam in 1946) as a draftsman. Chief engineer from 1932 and vice-president of research and development from 1956 until his retirement in 1963, he managed the staff designers and contracted design consultants. He headed the company’s parade of products that proved consistent, design-led market performance.

Jepson’s technical knowledge and understanding of consumer needs resulted in countless functional, long-lasting products. Sunbeam’s coffee percolators, fry pans, toasters and waffle makers, irons, personal shavers and hair dryers, fans and heaters, garden sprinklers, hedge trimmers, can openers, and clocks became staples of the American home. Jepson’s contribution to the development of the consumer products industry is unrecognized. In 1998 the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp featuring the 1930s ivory-colored Mixmaster with green glass bowls, in this small way acknowledging the impact of his work in bringing versatile, reliable, and convenient tools to the American home.

Author’s note: Our Housewares History blog series spotlights innovative problem-solving, creative entrepreneurs and landmark products of the past to inspire today’s inventors and companies. Launching a revolutionary new product is very risky; evolutionary changes are more common. Many creators of new products look at a traditional item and ask themselves “How can I improve how this task has been done for so long?” They think about new ways to solve the same problem and study past products to seek what alternatives have been attempted. Sometimes great product ideas struggle at first introduction because the market isn’t ready and then return years later in new forms that take advantage of new technologies or respond to new conditions. Classic products live on, evolving with incremental improvements as their time-proven designs continue to serve their original mission.

To learn more about resilience and innovation in the housewares industry, see America at Home: A Celebration of 20th-Century Housewares, a book published by IHA in 1997.