I photograph design specialist Asko Ahokas standing in front of a giant projected pipe. The picture references Hitchcock, with Ahokas’ tall hound’s-tooth suited form silhouetted onscreen. The wooden pipe in the background is unsmokable, its bowl non-existent. These are all fitting elements for a presentation entitled “Romantic and Practical” although its working title of “Practical and Poetic” was perhaps more fitting.

I photograph design specialist Asko Ahokas standing in front of a giant projected pipe. The picture references Hitchcock, with Ahokas’ tall hound’s-tooth suited form silhouetted onscreen. The wooden pipe in the background is unsmokable, its bowl non-existent. These are all fitting elements for a presentation entitled “Romantic and Practical” although its working title of “Practical and Poetic” was perhaps more fitting.

As Ahokas explains, global design trends for the next two years see us glancing nostalgically over our shoulders back to the ideas, materials and values all the way to the Victorian era. But we’re still practical, especially when it comes to housewares. So practical, there is a quiet robolution underway, with well-presented robots like the Grillbot and Winbot 7 Series helping us with daily chores.

“It’s all about biocentrism and biodesign – we are falling in love with life itself. It can be seen in so many ways,” says Ahokas. These include the use of colors; materials like glass, marble, leather and brass; new organic forms; the mutual design influences East and West are having on each other; cabinets of curiosities and a yearning for roots.

Fascinating conversation starters

Which brings us back to the curious pipe made by Turkish designer Soner Denurel. Ahokas describes this as an art-like object and likens it to the fascinators adorned by women at Royal weddings and horse racing. “It’s like a conversation piece,” he says. These objects are curiosities.

“These are the fascinators of the home. They don’t have a clear purpose but are homeware accessories that guests see; they stimulate conversation. They make you admire the host’s wit and inner world. That’s something we all want, we want to be seen as witty and smart – people who have understanding.”

The pipe also references color, a masculine counterpoint to the soft, feminine palette so in vogue. That palette calls on the sophisticated grays and powders of the ‘20s and ‘30s to deliver an elegance for which we yearn. In contrast, the brown of the pipe is strong, reminiscent of men’s rooms and paneled oak rooms; a style that is cropping up in collections like the racing-inspired Hermes Rallye 24.

Ahokas is not at all surprised that Emerald is Pantone’s Color of the Year, highlighting Norwegian designer Anna Talbot’s “Kiss me, kiss me, kiss me” necklace as invoking the “Lush, intense power palate of nature. Emerald is a central point, inviting scenery, nature and the forest to enter this new, exciting world.”

It’s a world that can best be seen through the sheerness of glass, and in urban planning glass is everywhere. Ahokas confesses that he feels blessed to be a part of the “schizophrenic world that includes the slow evolving trends of urban design as well as the fast-paced world of interiors and tabletop trends.”

Fragile influences

Fragile influences

In design, Ahokas guarantees glass will take the forefront as a material of choice among inspired young designers, both in mass- produced market and small boutique, craft items. He points to a recent exhibition in Stockholm, where a collection of mini glass designs was set against vivid, crane-like robots that gently policed the fragile glass pieces. He says: “The juxtaposition between modern forward thinking and fragile form giving is interesting, and points a direction to the future.”

It’s a future ironically fixed firmly on the past, a warm, nostalgic reaction to the cold, sleek aluminum revolution of recent years. Architects and designers alike are reviving the aesthetic of the ‘20s and ‘30s with warm brass and even leather. The lost art of Cuir Bouilli (boiled leather) can be seen in the collections of young designers like Swedish Sanna Svedestedt’s soft jewelry. Other revivers of the technique, like Simon Hasan, collaborate with design and fashion brands, creating everything from glass and leather vases to leather lamps glowing with strips of metal.

Form is also evolving, from the angular dynamic form that dominated the recent past to soft, rounded edges like those seen in the wall hooks Claesson Koivisto Rune made for Stockholm Studio.

Others are spinning the clock back even further, with marble. Anderssen & Voll’s marble and cast iron cooker is a good example – a piece so beautifully designed it is elevated to art.

Ahokas says: “We are back to the idea of unique collectible items that tell us something about ourselves. It comes from the 17th and 18th century cabinet of curiosities.” He explains that the line between craft and art is becoming increasingly blurred with designers creating limited edition items that are “very collectible.”

Cross-pollination

Art has a history of influence from diverse cultures, and Ahokas explains an “interesting dialogue between Europe and Asia” is currently occurring. “Inspiration is coming from Japanese design and Japanese thinking about housewares and tabletop design to European designers and brands as well as from Europe to Asia,” he says.

This can be seen in contemporary tabletop designs as well as in formal collaborations with designers using traditional Japanese techniques like Koubei-gama to create ceramics.

“It brings new energy, new blood,” he says. “Designers are exposed to these fine old methods, techniques and expertise and old manufacturers are exposed to a new kind of thinking and Western influence.”

“It brings new energy, new blood,” he says. “Designers are exposed to these fine old methods, techniques and expertise and old manufacturers are exposed to a new kind of thinking and Western influence.”

He points to a collection by French designer Inga Sempé, a striking set of dinner plates, and explains the complex process used to create the striated structure and pattern on each dish.

Lest we forget, Ahokas reminds us that our influences derive from nature, a notion that has developed into a full-blown resurgent trend he calls “back to the roots.” Ahokas is not just being figurative here. Pulling up a giant illustrated beet he talks at length about its virtues. “Our love affair with life itself manifests best when we look at nature and roots literally. It is just a reminder where it all starts.”

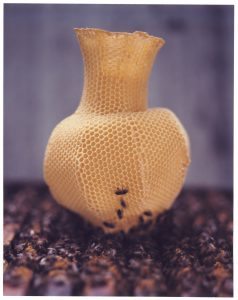

Designers mischer’traxler share this idea of harnessing the essence of nature and started a series of vegetable inspired resin moulds. Cast in gentle, warm tones the project initially hit a few stumbling blocks until collaboration with a Spanish firm ensured it safe for food. “This goes into the same family of ideas of us falling in love with nature and life itself. In comparison, Slovakian designer Tomas Libertiny’s effort is more of an artwork,”Ahokas says.

Using Libertiny’s bee vase as an example, he explains “Bees are everywhere. The end of the 1990s were the time of the butterflies, now it is time for bees. Bees are essential to life; they pollinate flowers. Libertiny reversed that idea, harnessing the bees to design a flower vase.”

“I’m fascinated by bees; they are a reminder of how fragile this ecosystem is, so it is understandable the bee has become a symbol of many things,” says Ahokas. Interestingly, a beehive lamp design by Finn Alvar Aalto dating from 1953 combines brass, and a soft glow.

Ahokas concludes with an image of Hubert Duprat’s work over the past quarter century, tiny golden insect larvae studded with semi-precious stones. These are made all the more remarkable by Duprat’s process: he gives living larvae precious metals, pearls and stones as building materials which they form into little, jewel- encrusted nests. A reminder of the value of nature?

“What wonderful examples of what they have won,” he says. “It’s a marvel and a reminder that design is not all human made.”

It’s a reminder of our ongoing love affair with nature.